Thank fucking Dr. Manhattan.

(Dis)Honesty – The Truth About Lies

There are still good ones out there. Keep the faith.

The take home from this film is that bankers are twice as dishonest as politicians.

Arrival

Should you watch Arrival? Yes. You should watch Arrival. This is the film Contact (“Whatever it is, it ain’t local.”–sorry Jodie) wanted to be twenty years ago.

Arrival begins with a trope best known from Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End, not to be confused with the television adaptation that, tragically, fell victim to the pitfalls of that format but is definitely still worth a watch. Twelve large coffee beans, obviously representing the Apostles, appear hovering at various positions on Earth and offer contact in the form of doors that open periodically to allow ingress.

This film caught us completely off guard. We remained deeply skeptical even after enjoying the first half of the film, but as the pieces clicked together, we were swept away by Arrival’s elegant undertow. If you are caught in a riptide, you should swim sideways. We let this one carry us out to sea.

We cannot say too much about the film, except that it depends on the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis. Our rudimentary understanding is that the language you speak defines the way in which you think. We are not linguists, but this does remind us of Marshall McLuhan’s theory that a medium that enables communication also structures, or limits, communication. (The DMS recommends this reader if you are unfamiliar with McLuhan.) Noam Chomsky’s work is heavily critical of the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, and it looks as though modern linguistic theorists (yes we know that Chomsky is still alive) are also skeptical.

We realize that we are mixing linguistic theory and media theory, but when you have a scumbag in office whose preferred method of communication is limited to 140 characters, it is worth thinking deeply both about language and the media we use to communicate. Arrival begs us to think deeply about these things insofar as it literally centers on our relationship with aliens. The message there is relatively overt.

To use an example from McLuhan, think about an automobile as a medium for communication. We built our country’s infrastructure around the automobile, and now we are finding it difficult and costly to change that infrastructure. Here at the DMS, we care about how people consume media and communicate. Arrival explores how we may be limiting ourselves.

Watchmen

After lying in furtive restlessness for hours the other night, this DMS member slid from underneath the covers, shuffled to the living room, and decided to re-watch the film adaptation of Watchmen. So now we know who watches them. Please tell Alan Moore. Maybe also check out Moore’s latest hit, Providence.

The DMS’s in-house doctor believes our rapidly increasing bouts with insomnia are a direct result of exposure to information about current events. Also past events. See Thompson, Hunter S., Better Than Sex: Confessions of a Political Junkie (1995); Thompson, Hunter S., Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72 (1973). Unfortunately, our esteemed doctor studied history before medical school, so she is not optimistic that a cure will be developed anytime soon.

As the media, correctly, churn out articles discussing one of two chilling Executive Orders signed by a scumbag on January 25, 2017, in-depth reviews of the same scumbag’s restructuring of the National Security Council appeared below the fold. Maybe it is the cognitive dissonance inherent in feeling nostalgia for the Bush administrations, but during this viewing of Watchmen, we got a bit closer to understanding Sally Jupiter’s refusal to hold a grudge against Edward Blake, the Comedian. We do not condone the Comedian’s many horrific acts of violence, but evidence is piling up that this life is a terrible joke.

We think the Comedian solidifies his opinion that, as Walter Kovacs repeatedly tells viewers, the end is nigh when Dr. Manhattan watches passively as the Comedian guns down a woman carrying his child in Vietnam.

Since we have copies of the comic books handy, we will quote the Comedian from his original rant directed toward Dr. Manhattan.

“You watched me. You coulda changed the gun into steam or the bullets into mercury or the bottle into snowflakes! You coulda teleported either of us to goddamn Australia[,] but you didn’t lift a finger!” (emphasis in original). Dr. Manhattan, a character with god-like abilities, does not care about humans in the Comedian’s view, and, well, the Comedian saw how terrible humans can be to each other.

In the film, Nixon has ruled with an iron fist for more than a half dozen terms. Democracy is a farce, and the audience is left with a question: Is Adrian the hero, or is it Kovacs? We are reminded of a passage HST wrote while covering the ’92 election:

“Some people will say that words like scum and rotten are wrong for Objective Journalism—which is true, but they miss the point. It was the built-in blind spots of the Objective rules and dogma that allowed Nixon to slither into the White House in the first place.”

After Nixon died, HST wrote “Richard Nixon was a warrior: He gave no mercy and expected none.

Yet he approved my first White House press pass and never had me busted for the horrible things I wrote about him.”

What would HST write about our current scumbag? He might have written a joke but not the laugh out loud kind.

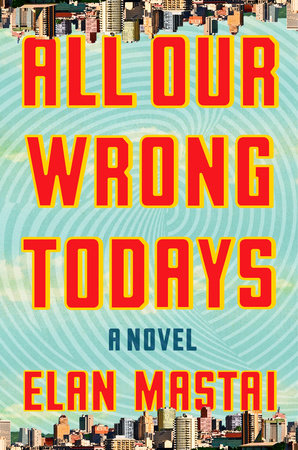

All Our Wrong Todays

One of the benefits of being kind to librarians is the occasional advanced proof of a book that feels written just for you. Sometimes, as is the case with Elan Mastai’s wonderful All Our Wrong Todays, these advanced copies even include a short note beginning with “Dear Librarian,” which makes even the Dystopian Movie Society feel intellectual and savvy.

Mastai’s stunning first novel is a break from his day job, writing movies. No wonder we here at the DMS fell in love. The main character, whose name I shall not print here for reasons that will become apparent if and when you purchase and read this book, is kind of a dick. Naturally, we can all relate to him.

The narrative begins in a utopian society, fueled quite literally by the invention of a device that harnesses the rotation of the Earth to generate unlimited clean energy. Because the inventor dies shortly after his proof of concept, he makes this technology free and open to everyone. Maybe we have watched too many films of a certain genre, or maybe we know too many human beings, but the DMS is deeply skeptical of the idea that unlimited clean energy would lead to the utopia described at the beginning of Mastai’s brilliant story.

The utopia readers see at the start of the book, however, is a prelude to the time travel narrative in which our protagonist becomes the first time-traveler, accidentally creates our reality as a dystopian alternate timeline, discovers the concept of temporal drag, and maybe loses his mind. It is phenomenal. Of the many differences noted between the teased utopia and our own world, my favorite was Kurt Vonnegut.

As the main character tells it, “Vonnegut’s writing is different where I come from. Here, despite his wit and insight, you get the impression he felt a novelist could have no real effect on the world. He was compelled to write, but with little faith that writing might change anything. . . . [I]n my world Vonnegut was considered among the most significant philosophers of the late twentieth century. This was probably great for Vonnegut personally but less so for his novels, which became increasingly homiletic.”

So it goes.

*

If you enjoyed Charles Yu’s How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe, you will love All Our Wrong Todays. Both deftly navigate the narrative pitfalls of branching alternate realities while somehow making the personal relationships explored in each book more important than their time travel plots.

Pre-order All Our Wrong Todays before we run out of tomorrows. Excerpts of the book, ready for public consumption on February 7, 2017, may be read here and here. Support great literature by buying this wonderful read here.

The Girl With All the Gifts

It is a fair bet that any film described by critic Jay Weissberg as “[a] tired attempt to board the zombie bandwagon . . . ” can happily hitch a ride with us. Sure, the film is a bit heavy handed at times, but maybe every fucking person in the United States should be slapped around a little bit. We loved the film, based on the book by M. R. Carey, and look forward to its release in North America.

Our favorite character is Melanie, a young black girl growing up in prison. If it is not thought provoking to see a group of heavily armed, mostly white people so terrified of a petite black girl that they keep her in Hannibal Lecter style restraints for most of the movie, then you probably live in South Dakota and think racism is something the Texas School Board of Education includes in children’s history books as a footnote somewhere near the hills of Georgia.

The narrative, and sometimes feel, of this movie draw favorable comparisons to The Last of Us, which finally convinced a lot of parents to throw in the towel and decide that video games might possibly be capable of artistic achievement. Both build on the not implausible idea that a fungus could give humankind a run for its money. We have not put up much of a showing lately, and, as it turns out, fungi have been carrying a lot more weight than we thought. The Girl With All the Gifts also shares some commonalities with one of Warren Ellis’s better recent comics, Trees, which is worth picking up at your local comic book shop.

The pacing is sometimes slow, following Melanie’s still-sharp mind as she attempts to make her way in the only world she has ever known. Rather than detract from the film, it evokes the same feelings this viewer had watching children dancing under sunlight in David Gordon Green’s George Washington. What Melanie realizes is that the “end of the world” just means “the end of humanity as we know it.” Frankly, that might be a welcome development.

As we recall, we have been promised that the world will never again be destroyed by flood. We do not remember any such promise with respect to fungi.

By the way, those zombies are what you look like visiting Times Square. Except the zombies move a lot faster and seem to have a goal in mind.

Morgan

Although an artistic director discussed adding a “human element” during his interview in the making-of portion following the trailer for Morgan, we here at the DMS still give IBM’s Watson credit for creating the chilling companion piece to SunSpring. A truly terrifying artificial intelligence (“AI”) would probably never let on that it existed. IBM’s Watson has failed in that regard (much like Olympic Games), but if we are to believe the marketing campaign accompanying Morgan, Watson created the trailer below by analyzing the film. Aside from the visual allusions to Silence of the Lambs and musical accompaniment from the Twin Peaks Children’s Choir, the most unsettling part of this trailer is that a computer created something so manipulative.

Borderline autonomous cars are gradually seeming more like an inevitability and less like a machine that might end up making kill decisions. At the least, the US, UK, China, Israel, Pakistan, Iran, Iraq, Nigeria, Somalia, South Africa, Hamas, and Hezbollah all have armed drones that fly through the air at their disposal. It takes little imagination to read Stanislaw Lem’s Fiasco and its featured planet, Quinta, with rogue autonomous defense systems as a forgone conclusion.

Stranger Things

While there must be close to 1,000 micrograms of nostalgia in each episode of Stranger Things, do not watch it because it triggers all those fuzzies from your childhood. Watch it because it is a fantastic show that ups the bar for content in a world where Two and a Half Men was consistently one of the most watched shows in the United States for more than a decade. Watch it because, much like Olympic Games, it plants ideas. Stranger Things happens to plant positive ideas about gender identity, people with different colored skin, and generally how humans should treat other humans. Unlike Olympic Games, Stranger Things mostly delivers its payload without detection.

With that disclaimer, we will indulge in a bit of nostalgia. If the only thing we know about something is that it is a bit twisted, we sometimes like to consume it in a non-linear fashion. The first episode we watched was the fifth, which we were told was the penultimate episode. Still thinking we had watched the second to last hour, we watched the first episode before watching the surprisingly long (to us) conclusion. Then we went back to the beginning and watched the initial installments sequentially. Consuming media is not something we do for fun, we do it to probe our physical, emotional, and intellectual limitations. In this case, it was like eating dessert first when your parents were not paying attention.

Set in 1983, the real evil confronted in the series is a human with an all-too-real backstory. The period-correct brands and references up the score on the realness scale even as Akira-level madness starts to mix with a narrative that will remind you of Flight of the Navigator, ET, The Dark Crystal, and several other experiences from your childhood. Our non-linear viewing method led us to believe the narrative would end up in an extremely dark place. The parallels with Grant Morrison’s recent 6-issue comic book series, Nameless, and the story scattered across Reddit one chapter at a time by a user named 9MOTHER9HORSES9EYES9 are a bit on the nose. It does not get that dark.

The end, in fact, is in many ways extremely uplifting. One of us found ourselves sobbing because of one character’s flashbacks and his own memories of a younger sibling who was not expected to live. There are a lot of positive messages packed into this narrative. One of the reasons we focus on dystopian films is that by learning more about the way our world works, we hope to avoid the versions of the future (or past) that we see reflected in such films. Is it naive to think that the more we learn about how terrible humans are to each other, the better the world becomes?

Kids of the Apocalypse

I hope this is what teenagers are into these days. Aside from the music and the ill-fitting heteronormative message appended to this video, this short has some rad Congress-type animation and encourages children (primary demographic?) to think critically, or, at least, keep the faith.

Rødhåd – A Dystopian Journey

Maybe it’s because the acid had me thinking that an AI has taken over and we’re just pieces of meat waiting to die, but Rødhåd’s 8-hour set at Bunker last weekend felt overtly political. Always dance like it is the end of the world, but please be respectful. Etiquette matters. Especially in our final moments.